In conversation with Nobutaka Aozaki, a New York-based Japanese artist

Photo: Brad Ogbonna

Part of what New York has to offer — the trash, the rats, the rent, the subway, the laundromats — it’s all sort of formative and part of New York’s charm. But imagine yourself as an immigrant with English as your second language trying to navigate the nuances and unpredictable nature of New York City — New York’s difficulty just became a lot more layered. Some people are lucky enough to have a network of friends or family to teach them much-needed survival skills. Others learn by trial and error. Many don’t make it at all and leave the city in defeat.

Nobutaka Aozaki, a Japanese artist based in New York City, has his art to lean on. His art form is interactive and is often based on engagement with complete strangers he meets on the street. For one of his works, From Here to There (Manhattan), he posed as a tourist and asked New Yorker pedestrians to draw maps with directions for him. He collected and aggregated these small individual maps that then culminated in a contiguous map of Manhattan.

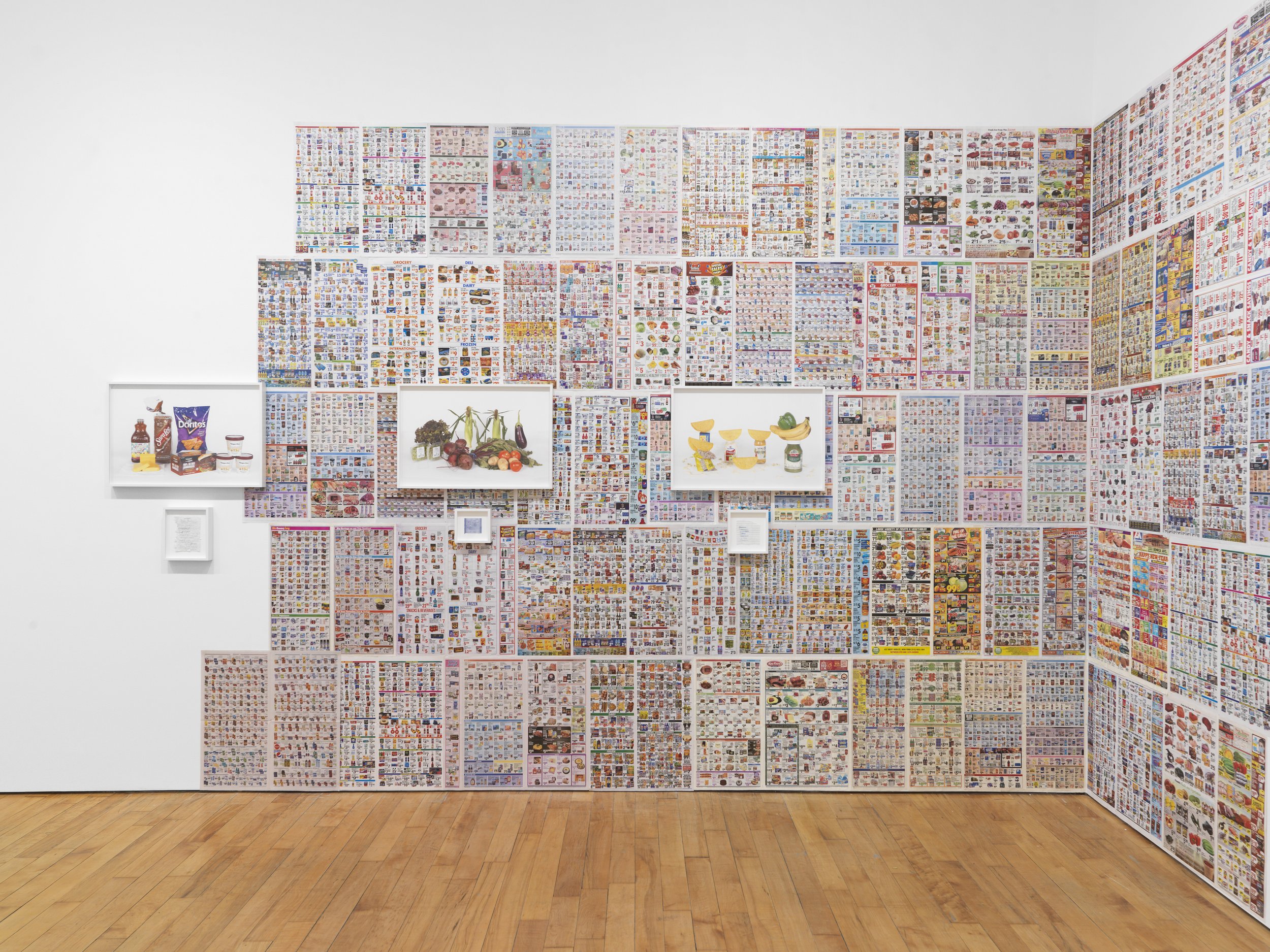

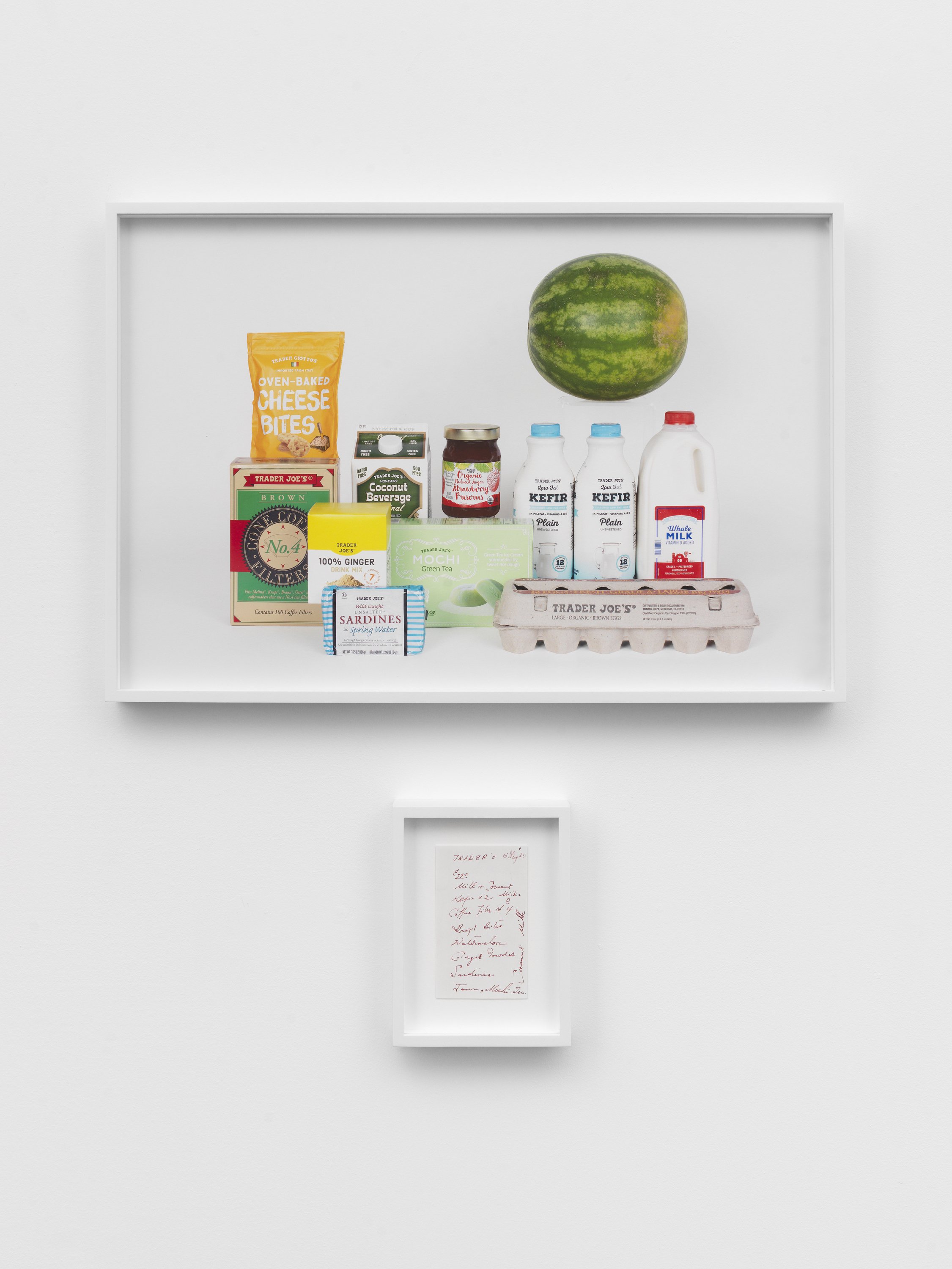

Aozaki’s latest exhibit, Grocery Portraits, is now on display at Marinaro, New York in Manhattan. In this series, the artist collects random shopping lists from the streets of Manhattan, purchases the listed items, and photographs them as a still-life portrait. The lively photographs assume the personality of the mysterious listmaker, conveying aspects of the cultural habits of the city’s diverse population. Grocery Portraits is open to the public until February 4, 2023 at 678 Broadway, Floor 3.

Aozaki completed his MFA at Hunter College in 2012. His work has been shown internationally and locally here in New York City at the Whitney Museum and the Brooklyn Museum, among others.

I spoke with Aozaki about his art and his time in New York. These are edited excerpts from our conversation.

Tell me about your childhood and hometown.

I was born and spent my childhood in Sendai city (now the city is a part of Satsumasendai), a small city in Kagoshima, the southern prefecture of Japan. The city is surrounded by a rich natural environment but it also has some large industrial factories such as the Sendai nuclear power plant, the Kyocera electronic and ceramics plant, and the Chuetsu Pulp & Paper factory. My father worked as a public officer at the city hall. As a kid I enjoyed wandering about and finding insects in the woods or shells on beaches, looking at encyclopedias, remembering names, and drawing them.

How did you discover your love for art and did your parents support you becoming an artist?

I worked as an editorial assistant in the publishing department of a newspaper company in Kumamoto City. Through this job, I met many creative people such as writers, designers, musicians, and cartoonists. It was an intellectually stimulating environment. Some colleagues and I made a monthly art zine for fun and distributed it to local bars and cafes. We also made some woodblock prints, music, and performances together. Through these collaborations with friends, I learned the joy of making things, and my motivation toward becoming an artist grew.

My parents were supportive, although, they wanted me to have a more ordinary and stable job than that of an artist. Living in the countryside where there is not much contemporary art, my parents have had a hard time understanding what I do as an artist. One day I hope to invite them to New York City and take them to museums and galleries so they can learn about the many things that could become art rather than the typical paintings or sculptures.

A lot of your recent art has focused on interactions with random people and/or things you find on the street – why is that and how would you describe your overall approach to art?

I like to make art through discovery, serendipity, mysteries left on the street, and the collective imprinting of people and communities. New York City is filled with surprises, and I feel most excited to rely on the unpredictability of my daily encounters in the city. I frequently combine performance and found objects, developing from my everyday interactions with people on the street and chance encounters with ephemera that have traces of humans. I conduct fieldwork in the city and collect traces of this contact as evidence of myself and others as well as cultural materials to study social economical cultural aspects of places and subjective perspectives of people. My work takes collective, participatory, anthropological approaches.

For your latest solo exhibition, Grocery Portraits, what do you think the shopping lists reveal about each person? What do you think they say about New Yorkers in general?

Photos courtesy of the artist and Marinaro, New York.

Grocery Portraits are based on shopping lists that I find on the street. I shop for the groceries that appear on the lists, photograph them as portraits of unknown persons, and then experience them by cooking and eating. The personalized list of food items becomes cultural material to study and explore the neighborhood in which I find the list. The shopping lists, each with their distinct handwriting in different languages, give a fascinating glimpse of the lives of people in various neighborhoods in the city and convey something of the cultural habits and personal qualities of the city’s diverse human inhabitants. As there are many different characteristics between people, ethnic groups, and socioeconomic classes who live in New York, this project aims to evoke audiences' culinary empathy and give them a space to reflect on their family histories and cultural contributions/exchanges and learn about others.

How did this project impact your own Asian American experience? Did you find any new foods or products you love?

In this project, I cook and eat the groceries after I photograph them. Since I started this project I have experienced a variety of foods and culturally specific items I personally had never purchased and cooked or used myself before. I usually go to Japanese grocery stores to buy foods that I am familiar with or go to the same supermarkets nearby my apartment but this project gets me out of that habit and makes me more open and curious about different places and cultures. For instance, I have researched recipes as well as histories about the grocery items of other cultures and made dishes like matzo ball soup, sofrito tacos, and bacalao salad. I wouldn’t have cooked them without this project and they all tasted good and interesting.

In a previous exhibit, Clocks for Immigrants, you talk about the feeling of being in two places (two times) at once, the state of mind of immigrants – can you elaborate on your own experience?

At first glance, the clocks look like regular clocks but if you look closely they have two hour hands. Those hour hands tell the times of different countries or places simultaneously. The clocks are not only practical clocks (although they are a little confusing), but they are also portraits of people who think about their homes in different time zones.

If you live far from your native country you often think about your family and friends in different time zones, especially when they are having a hard time because of events like natural disasters, industrial accidents, and wars. I felt this feeling of dislocation strongly when the earthquake happened in Japan in 2011. I was in New York and all I could do was imagine all day long what those across the globe may have been experiencing. The piece relates to this feeling of dislocation and longing.

What brought you to New York?

I chose to study art here because many artists and musicians I admired lived and worked in this city. I was particularly looking at the works of Andy Warhol at that time. As I had experience working as a printer at a commercial silkscreen printing company in Japan, his work was very interesting for me to think about the relationship between art and consumer culture.

How long have you been living here and what’s your experience been like?

It has been 17 years. It’s been like riding a roller coaster. Because New York is so expensive, I struggle to secure funds for both living and my art practice. Thankfully, I was able to sustain myself as an artist with the help of grants and residency programs from several art organizations. Friends and family also help me to get over some difficult moments.

Compare and contrast the experience of living in Japan where you were the majority versus living in America where you are a minority.

Japan is still a relatively racially homogeneous nation, so I never had to think about the language I speak or my Japanese-ness (Asian-ness) in relation to other languages or cultures when I was there. However, after moving to New York City, one of the most multi-ethnic cities in the world, I was shocked by the variety of cultures, races, genders, and classes I was suddenly surrounded by. In the beginning, it was difficult living in this entirely new cultural environment with many confronting language barriers. I felt I had become a baby or an alien from another planet because of my lack of English skills. Because of that, I have become very sensitive in small everyday interactions. Even the most mundane interactions, such as grocery shopping, buying a cup of coffee, or asking directions, became really challenging and significant. I have also become aware of the importance of respecting the differences and similarities of others in order to collectively live in this diverse world. These experiences of living in New York have made a strong impact on my work.

How has your time here in the United States influenced your art and perspective?

I came to live in New York City, hoping to meet people from all over the world and expose myself to others' cultures and ideas. Since then, my practice has changed dramatically through these cultural encounters and the experience of living in a foreign country. My work now engages more directly with people in the city and focuses on creating a place for dialogue between different cultures.

What do you hope to achieve as an artist?

My artistic goal is to help create a world that is more open to diversity – one that cares about minorities by finding spaces for imagination within this homogenized society. I conceive my projects in order to spark imagination toward others, communication, and connection between diverse groups. I hope my work demonstrates how art can investigate cross-cultural understanding and exchange, and encourage audiences to feel our interconnection. For this purpose, New York is an ideal place and subject to explore as it is the most ethnically diverse urban city in the world.

5 Rapid Fire Questions

Which Japanese restaurant in New York City reminds you of home?

What’s your favorite Asian snack?

Red Bean bun

Pick one: ramen, soba, or udon?

Ramen

Who is your favorite Japanese musician?

What’s your favorite street in New York City?

Broadway